by Rabbi Noam Raucher, MA.ed

Purim is one of my favorite Jewish holidays. I love how much our faith takes the idea of irreverence into spiritual practice. We all need a chance to let go and “act a fool,” as Ludacris says. Sometimes, we all need permission to let go of the necessary strictures for everyday life. It feels safe to do so for that brief 24 hours that Purim exists. It helps us to lift our heads a bit and breathe. It’s like a spiritual forgiveness or trip out to Vegas: What happens at Purim stays at Purim. That may be a helpful philosophy at times. However, I would like to know if Purim’s release can be applicable throughout the year. Particularly as Jewish men return to their everyday lives, putting back on masks that have nothing to do with celebrating Purim.

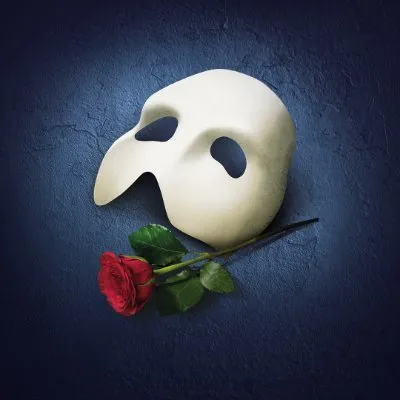

Hidden miracles and a sense of concealment mark the events of the Purim story in the Book of Esther. Wearing masks and costumes symbolizes the secret nature of the events in the Purim story and reflects that things are not always as they seem. Thus, Purim should be the natural time by which synagogues and Jewish communities offer men a chance to shed their masks and share what’s underneath—revealing the heavy masks they carry around for acceptance and what is hidden beneath the mask for fear of rejection.

Men, like individuals of any gender, may wear various metaphorical masks to navigate social situations, cope with emotions, or conform to societal expectations. Here are several types of metaphorical masks that men specifically might wear:

The Stoic Mask: Men are often socialized to suppress emotions such as sadness, fear, or vulnerability and to present a stoic and unemotional exterior. This mask can lead men to hide their true feelings and project an image of strength and resilience even when they struggle internally.

The Provider Mask: Society often pressures men to be financial and emotional providers. Men may feel compelled to wear a mask of success, competence, and self-sufficiency, even if they are experiencing challenges or uncertainty in their roles as providers.

The Tough Guy Mask: Men are culturally expected to be tough, resilient, and unyielding in adversity. This mask can lead men to suppress vulnerability and sensitivity, instead projecting an image of toughness and invulnerability to fit societal norms of masculinity.

The Masculine Ideal Mask: Society often promotes a narrow definition of masculinity that values traits such as aggression, dominance, and sexual prowess. Men may feel pressure to conform to this idealized version of masculinity, even if it means suppressing aspects of their true selves that do not align with these expectations.

The Work Mask: In professional settings, men may wear a mask of confidence, authority, and competence to assert themselves and advance their careers. This mask can lead men to prioritize their professional identities over their well-being and may contribute to feelings of stress and burnout.

The Father/Husband Mask: As fathers and husbands, men may feel pressure to embody the roles of protector, provider, and authority figure. This mask can lead men to prioritize their family’s needs over their own and suppress emotions or vulnerabilities that they perceive as conflicting with their roles.

Consider how good it feels to be understood and accepted for who you are. We all strive for this. And if we are emotionally aware, we know that people who give us the space and time to be seen and welcomed are doing so without legal obligation. In a world that doesn’t care about how people feel, it’s an act of generosity to provide space for someone to show a more authentic side of themselves than they usually would. Mainly to allow them to share without judgment or shame but with respect and dignity.

It’s scary to think about what happens to the men wearing their masks constantly. After a while, those projected personas become the real thing. The providers will sacrifice and impoverish themselves to appear stable without asking for help. The tough guys don’t know how to be vulnerable and never let anyone in.

For me, it’s the mask of being a mensch. We usually tout this persona as “being a good person.” But as a boy and man, that’s often translated as “the guy who can handle everything and anything all at once.” That man is the dedicated father, the good son, the successful CEO, and the stoic and master of his craft. But does any of that leave room for error or failure? And as a divorced man, it’s easy to feel inadequate when it comes to failing at family life- a central part of Jewish culture.

It’s no surprise then that Purim asks us to be more generous than we usually would by delivering gifts to friends (mishloach manot) and those in need (matanot l’evyionim). The generous space we are given to take our masks off, in turn, creates a generosity within us that we want to share with others. I can’t think of a better opportunity to provide for Jewish men. Think about how much more giving, kind, and brave Jewish men could be to lead from a place of vulnerability and empathy if they had regular places to shed external expectations of what it means to be a man.

Take this Purim holiday to give your son, brother, father, husband, boyfriend, or any other man in your life that you care about an opportunity to share what they cover up and projects for acceptance as a man. You, or your community, could take the time to hold space for this man. Here are two activities that may help:

1. Share the list of masks here and ask them to find one (or two) that they identify with. Then, give them a chance to share what that mask is like. And then reassure that man that what’s under the mask is what’s most welcome to you.

2. You can also use and share this helpful digital worksheet from the Million Mask Movement to articulate your mask. Ashanti Branch, a high-school teacher, created the Million Mask Movement.

We all want men to be more emotionally intelligent, vulnerable, and kind. I do not doubt many men will respond to this opportunity with fear or dismissal. It threatens their understanding of masculinity and identity. Let’s give them a chance to discuss what might prevent that. In doing so, you will honor their authentic and loveable parts throughout the year, and not just on Purim. Without a chance to remove those masks and know their masculinity remains intact, we risk becoming like the central character of the book The Knight in Rusty Armor by Robert Fisher. Instead of the mask being a temporary protective guard, it becomes the hardened shell a man lives in permanently.

Need technical or website help? Email us at

Copyright © 2025 Federation of Jewish Men's Clubs. All rights reserved. Website designed by Addicott Web. | Privacy Policy