by Rabbi Noam Raucher, MA.ed

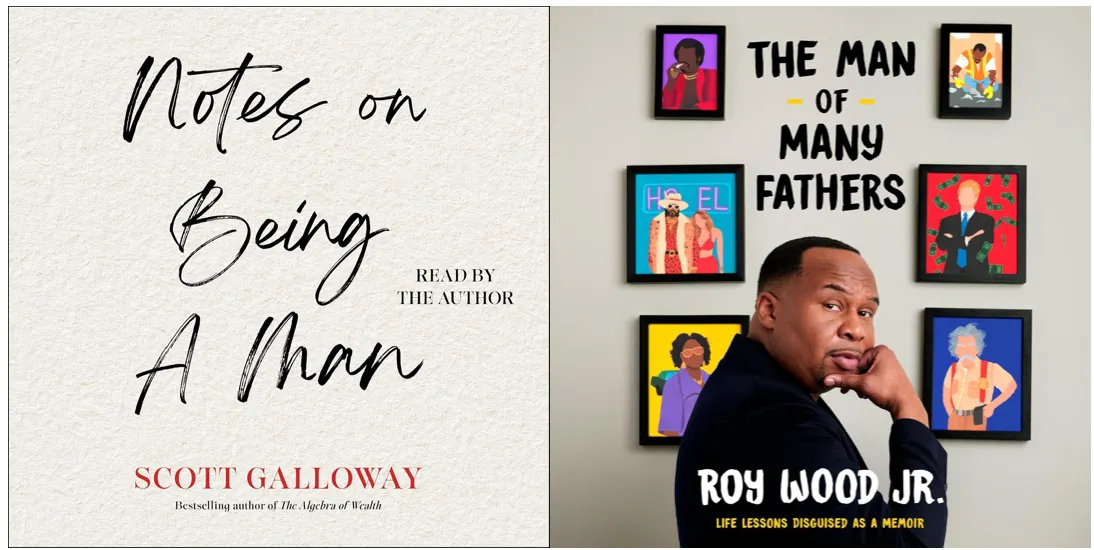

Scott Galloway’s Notes on Being a Man and Roy Wood Jr.’s Man of Many Fathers arrived within months of one another, each attempting to answer the same urgent cultural question: What does it mean to be a man today? Both authors write out of personal experience shaped by nontraditional homes, complicated fathers, and the fractured social landscape facing boys and men in the twenty-first century. Yet the books could not differ more sharply in voice, method, emotional register, and the moral imagination they invite their readers to inhabit. Read together, they offer a revealing contrast — not only in how two public figures narrate their own coming-of-age, but in what each believes men now require in order to flourish.

Galloway’s work announces its intent early: he will confront the statistical realities of male loneliness, academic freefall, unemployment, addiction, and suicide, and then use episodes from his own life to illustrate those trends. He positions himself as an embodiment of what the data implies a “successful” male trajectory can look like — someone who has outperformed the negative slope lines defining men’s contemporary struggles. His book often reads like a handbook of principles for young men, delivered in the brisk, prescriptive voice familiar to readers of his previous work.

Yet the effect, despite the gravity of the material, is oddly bloodless. Galloway’s anecdotes — such as a trip to buy ice cream with his father and father’s girlfriend — are meant to illuminate broader truths. But they rarely expand into emotionally textured reflection. Instead, they serve as pivots to behavioral dicta: be a provider, don’t be cheap, always pay for the date. The prose is crisp but curiously affect-neutral, as if an especially earnest algorithm were attempting to reverse-engineer masculine wisdom from case studies.

Roy Wood Jr.’s Man of Many Fathers is the exact opposite kind of book. Woods writes as a storyteller, not an instructor. Each chapter introduces a man who shaped him: a father who chased bargains across multiple grocery stores, comedic elders who offered hard-won advice, colleagues whose struggles forced him to reckon with his own vulnerabilities. Wood’s reflections are often hilarious, but never glib; they turn easily toward grief, confusion, awe, and unexpected tenderness. When he recounts the suicide of a fellow comic, the lesson he draws about joy and the labor of comedy emerges from lived sorrow rather than sociological abstraction. Placed side by side, Galloway’s book feels brain-forward — sometimes impressively so, often exhaustingly so — while Wood’s feels soulful, inhabited, and deeply human.

Both authors wrestle openly with the legacies of their fathers. Galloway revisits episodes of embarrassment, scarcity, and what he interprets as paternal missteps; from these he extracts axioms about the importance of financial generosity and reliable provision. Wood similarly tracks lessons from his father, but the tone diverges immediately. His father’s obsessive attention to prices — driving between multiple stores to secure cheaper eggs or slightly smaller milk containers — becomes not a rebuke of paternal failure but a meditation on frugality, care, and the emotional meanings embedded in thrift.

Both writers endorse the idea that men should pay for dates. Yet Galloway frames this as a transactional marker of male responsibility and attractiveness, while Wood frames it as something learned inside a network of family expectations, mutual obligation, and the desire to be seen and appreciated. Where Galloway distills masculinity into “provide, protect, procreate,” Wood treats masculinity as something far less formulaic — something pieced together through failures, reconciliations, and community belonging.

What neither book addresses — strikingly — is how these men navigate the demands of fatherhood within their high-visibility, high-pressure careers. Both are public figures with punishing professional schedules. Neither offers reflection on how they balance travel, media cycles, performance demands, and the emotional labor of parenting. This absence is not a flaw so much as a limitation: both authors position fatherhood as morally weighty, yet the practice of fatherhood under the constraints of celebrity remains largely unexamined terrain.

The omission is significant, for in a moment when many men struggle to reconcile work with relational presence, these authors’ silence mirrors a broader cultural blind spot: we valorize fatherhood but rarely interrogate how men, especially successful ones, actually live it.

Each author chronicles the mischief and mistakes of adolescence and early adulthood — drug and alcohol use, academic lapses, heartbreak, and impulsive acts. But again, the nature of the storytelling reveals divergent moral worldviews.

Galloway recounts his academic derailing at UCLA — failing his fourth year, nearly failing his fifth, and depending on a self-exonerating letter to secure leniency. The episode is framed as typical youthful immaturity. What is missing, however, is the sense that anything deeper than embarrassment was at stake. The story confirms his thesis that young men are “like dogs” who must burn off energy through exercise and moderate their weed and alcohol consumption. But the narrative lacks genuine reckoning; the consequences remain largely abstract.

Wood’s college crisis, by contrast, is existential. After being caught stealing credit card numbers from the post office where he worked, he confronts not only the legal system but the racialized hostility of law enforcement. The lessons he draws — self-advocacy, accountability, humility before the court — come not from a clever letter, but from the moral and psychological labor of confronting his parents’ expectations and his own potential derailing. The event becomes a turning point that sets him on a more disciplined and accountable path.

Perhaps the most consequential divergence appears in how each author defines the endpoint of male development. Some of Galloway’s prescriptions — “Get out of the house,” “Be kind,” “Be good to the mother of your children” — all orbit a logic of surplus value. Kindness matters because it produces positive returns. Discipline matters because it improves performance. Contribution matters because society rewards it. Even the inherent message, which amounts to “If you can’t add value to the world, get out of the way,” frames male worth in terms of utility. It is a worldview sharpened by market logic: the self as an asset to be optimized.

Wood offers no such calculus. The stories that shape him — stories of heartbreak, failure, joy, paternal absence, communal care, missteps, forgiveness — culminate in a quieter but far more profound claim: that a man’s worth is defined by his own voice, moral clarity, and capacity for care, however imperfect. Masculinity here is not a function to be performed but a self to be cultivated, slowly and with the help of many teachers.

Notes on Being a Man and Man of Many Fathers are both sincere contributions to the national conversation about men, boyhood, and responsibility. Galloway provides a map of the crisis, complete with data, directives, and a hard-nosed pragmatism that some readers will find refreshingly direct. Wood offers something different: a deeply felt narrative of becoming, guided by fathers both literal and symbolic, rendered through humor, ache, and unvarnished honesty.

Galloway writes as though masculinity can be reverse-engineered. Wood writes as though masculinity must be lived into. Galloway challenges men to add value; Wood challenges men to recognize their own. It is Wood’s book, ultimately, that lingers — because it offers men not instructions, but self-worth.

Need technical or website help? Email us at

Copyright © 2026 FJMC International. All rights reserved. Website designed by Addicott Web. | Privacy Policy